He Began to Die When He Was Twenty-one

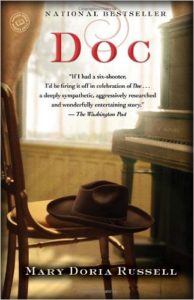

Forget every stereotype you may hold about Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. Forget you may not even like “westerns.” Read Doc, the 2011 historical novel by Mary Doria Russell: you’ll be richly rewarded.

Forget every stereotype you may hold about Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. Forget you may not even like “westerns.” Read Doc, the 2011 historical novel by Mary Doria Russell: you’ll be richly rewarded.

No need for me to add another in-depth review to the many enthusiastic ones found in the Washington Post, the Washington Times (they agree for a change), and in a dozen other publications and 36 screens worth of reader comments on Amazon. Instead, in the course of several blog posts, I’ll dissect a few passages that especially intrigue me.

If I love a book, I’ll read it a second time as a writer, asking myself how the author manages to make me cry or laugh or keep turning pages far past my bedtime. It’s how I hone my own craft.

In Doc, Russel uses the omniscient voice. That’s where the author is the narrator, the all-knowing guide who dips in and out of different characters’ heads and tells the reader things about them they don’t know about themselves, and who interjects her own opinions about their circumstances, motivations, and the setting in which the story unfolds, present, past and sometimes future.

I’ve never tried writing from this point of view myself—too intimidating. You have to be cocksure of your ability keep the characters straight in your readers’ heads, and confident that your narrator’s voice is entertaining enough to justify taking the reader on excursions outside of your character’s heads and your main story line.

Here’s an example from Doc. In the middle of an episode involving Johnnie Sanders, a young Indian-black half breed who’s a whiz at cards and later, the victim of a murder, Russel drops this bit of interpretive history:

“Johnnie Sanders’ daddy had told no lies. The Indians were crazy gamblers. For numberless centuries and uncounted generation, the Choctaw, the Zuni, the Crow, the Arapahoe, the Navajo, the Dakota, the Mandan, the Kiowa, and a hundred other tribes had whiled away countless days and nights playing a thousand games, betting on anything with an outcome that was not assured. Blame boredom. Blame the timeless unrelieved monotony of land so devoid of tress that owls burrow in the ground for want of better accommodation. Blame vast herds of ceaselessly chewing ruminants who walked with the unsyncopated beat of a Lakota chant. However you explained it, never and nowhere else on earth had gambling occupied the attention of so many for so long as in this flat and featureless land.

Then in a geological instant—just five years’ time—the American bison had been replaced on the prairies by European domestic cattle. Dead red Indians made way for live white bankrupts lured west by the promise of a fresh start on land free for the grabbing. Kate had watched it happen and felt no pity. The Indians all but wiped out? Good riddance. A danger eliminated, nothing more. Millions of buffalo rotting on the plains. Who cares? They were filthy brutes, huge and stupid.“

Neither Johnnie Sanders nor his daddy have any clue about all this; it’s clearly the author speaking. Does this daring tangent take you out of the flow of the narrative? It didn’t for me. I found it nearly as riveting as the story itself, a way of looking a Plains Indians I’d never considered.

But note how, in the second paragraph, Russell brings us back into the head of Kate, Doc Holiday’s partner and lover, so we see the tribes’ decimation through her uncaring eyes. We’re back into the story again, having enjoyed the brief side trip into history—a well written one at that.

Moral: If you’re going to use the omniscient voice, make sure your side tracks are compelling and your story train returns to the main track without much delay.

Doc Holliday’s grave in Glenwood Springs, CO.

Next: Boxing on the frontier